The Wagnalls Memorial

On May 30, 1925, Mabel Wagnalls Jones dedicated The Wagnalls Memorial in honor of her parents, Adam and Anna Willis Wagnalls. Adam was the co-founder of the publishing giant, Funk & Wagnalls. Both Adam and Anna were born in log cabins in Lithopolis, Ohio. Mabel knew it had always been Anna’s dream to do something for the little village which had never had anything done for it and to provide opportunities not available to her as a child. With the building of The Wagnalls Memorial, Mabel would fulfill her mother’s dream.

Mabel, an author and a concert pianist, had a special fondness for her parents’ birthplace. Though she never lived in Lithopolis (she lived most of her life in New York City), she visited it from the time she was a small child to spend time with her grandmother who lived in the village.

At the dedication, as Mabel was giving the deed to the town, she said, “Now this is our deed and I hand it over with no admonishments at all, because I know you will guard our building and use it wisely. My only hope is in using it you will find as much joy as I have found in giving it.”

Building the Memorial

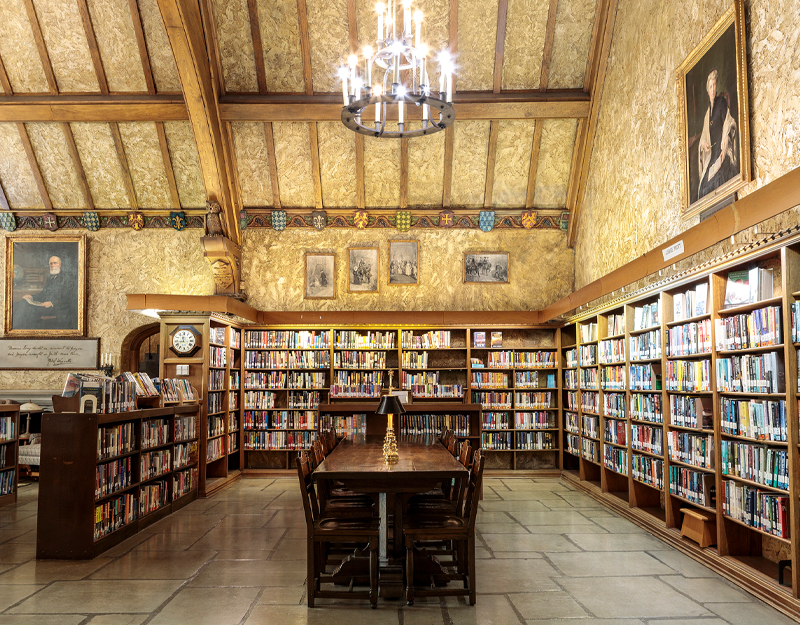

The architect Mabel hired was a local Columbus man named Ray Sims. Mabel’s husband, Richard Jones, worked closely with Mr. Sims. Most of the workmen hired were from Lithopolis, and most of the stone used was quarried from just behind the building site. As Jones stated, “That is really one of the wonderful parts of the whole story of Lithopolis. As nearly as possible we used local men and materials in construction. Every workman in Lithopolis worked for the love of the thing he was creating. Possibly not since the days of the Guilds has so much genuine interest gone into the erection of a building.” Success magazine in its September 1925 publication called it “the finest Tudor-Gothic structure in America.”

Social Hall

It was important to Mabel that the Social Hall have a fully functional kitchen and a pantry filled with the necessary pots, pans, china, and silverware. There were approximately 300 place-settings of china, and the space cost $3.00 to rent in 1925.

Mabel spoke at the building’s dedication when she accepted a silver Loving Cup filled with roses given to her by the village. She stated that when the plans were designed, there was talk of combining the auditorium with the social hall, but Mabel was adamant that the two should be separate, remembering from her childhood all the church dinners the women had put on and how they had to haul all of the food, tables, and tableware to make it happen. As she put it, “We finally split the difference by letting me have my own way…when you are admiring this building and enjoying the library and auditorium, praise my husband and Mr. Sims, but when you are carousing downstairs, please remember me.”

Paintings and Memorabilia

Paintings that were used as covers for Funk & Wagnalls’ magazine, The Literary Digest, adorn the walls of the Rager Reading Room. Two original Norman Rockwell paintings are on permanent display near the Patron Services Desk. Also on display are letters Mabel received from the author O. Henry while she was staying with her grandmother in Lithopolis.

The Gardens

Stroll the pathways in our garden to admire the rock sculptures and martin house of Dr. Edward Roller, a beloved local doctor who formerly resided on the land where the 1992 addition now stands. He collected rocks from all over North America and used them to create bird houses, vases, and other structures.

In 2016, The American Legion Post 677, invested in the gardens creating The Walker-Hecox-Hickle Gardens.

Formal Entrance Hall

This is the original entrance area of the building from the street. A “Tribute of Love” stone plaque dedicates the building to Lithopolis and Bloom Township in memory of Mabel’s parents.

The Tower

The lower tower room was set apart for the writings of the famous poet, Edwin Markham, a close family friend. The poems that were displayed in the tower room were written in his own handwriting. The upper tower room was set aside to display the paintings of John Ward Dunsmore, another personal friend of the Wagnalls family and their official portraitist. The upper room of the tower is now used for storage, and Dunsmore’s paintings can be seen on display in the original library and auditorium foyer.